17 Jul 2025

The Future of Education with Louka Parry

Length: 1:13:35

In this webinar, globally recognised educator and futurist Louka Parry explored education as a dynamic ecosystem—one that nurtures human potential and wellbeing in a rapidly changing world. He discussed how schools can be reimagined as environments where learners thrive, connect and grow with purpose.

The conversation focused on the role of AI in the future of schooling and how AI can be meaningfully integrated into education .

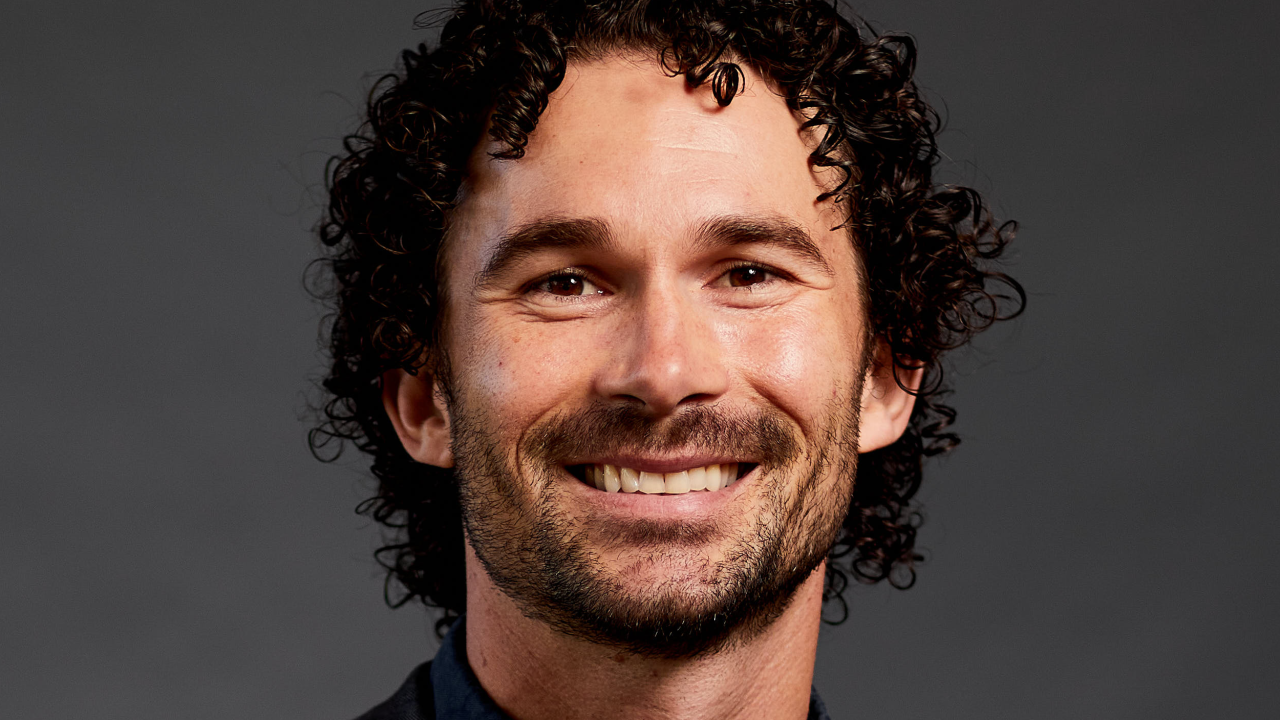

About the presenter

Louka Parry

Idea Curator. Learning Futurist. Global Strategist. Believer that the future belongs to those who constantly and rapidly unlearn and relearn in their daily work and life.

As one of Australia's top innovators Louka Parry speaks on futures, leadership, education, and transformation; having worked with thousands of leaders and educators from diverse contexts across the world, including in high-level policy fora such as the OECD, UNESCO, the European Commission, and with all Australian States and Territories. An award-winning educator, speaker, facilitator, and adventurer, Louka’s powerful ability to communicate ideas with clarity allows him to guide thinking about learning, leadership, and life to new places, earning him a place in 2022 as a Top 100 Innovator for Australia.

A rapid learner, Louka speaks five languages, has visited over 80 countries, holds two Masters degrees, has completed studies at Harvard and a residency at the d.school at Stanford and became a principal at 27 years old.

Download

Transcript

AMY PORTER:

We're good to start. Hello, everyone, and welcome to today's Thought Leadership webinar on the future of education with Luca Perri. My name is Amy Porter, and I'm a principal in residence with the Academy's Leadership Excellence Division. And I in particular look after the principal programs at the Academy. Just a couple of things to note about how the webinar will run. We're using WebEx webinar. So, there's no chat function, but we encourage your participation by submitting questions via Slido. A link was emailed to you last week, so just checking your email inbox to join Slido and enter the code and vote and ask questions. And what we'll do with those questions, we'll collect them up and then we'll ask at the end, give you an opportunity to respond to the most common questions. So, the session is being recorded, but your videos are not visible to anyone. And the session will be made via the Academy website. So, if you've got any colleagues you'd like to recommend it to, that would be amazing.

At the conclusion of the webinar, a QR code will be displayed for you to provide feedback on today's webinar. There's only three questions and so we encourage you to complete it and support our continuous improvement. I have the pleasure of the acknowledgement of country today. I am on Wurundjeri country at the Academy's 41 Saint Andrew's Street Centre so to begin the webinar, I'd like to acknowledge the traditional owners and custodians of all the lands on which you are joining us today. I pay my respects to elders past, present for they hold the memories, the traditions, the culture, and have been teaching and learning on these lands for tens of thousands of years. And I'd also like to acknowledge anybody that is joining us today who is of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background, and pay our respects to you as members of our education community. We express our gratitude in the sharing of this land, our sorrow for the personal and spiritual and cultural costs of that sharing, and our hope that we may walk forward together in harmony and in the spirit of healing.

So we're here with Louka Parry, and I'm thrilled to introduce him to you to present tonight's Thought Leadership Series webinar on the future of education. Louka is one of Australia's top innovators and a renowned speaker on futures leadership, education and transformation. Having worked with thousands of leaders and educators from a diverse context across the world, we were just having a chat to. He also speaks multiple languages and is currently learning Mandarin, which is pretty amazing. His powerful ability to communicate ideas with clarity allows him to guide thinking about learning, leadership and life to new places, earning him a position in 2022 as a top 100 innovator of Australia. A rapid learner, he has visited over 80 countries, holds two master's degrees and has completed studies at Harvard and a residency at Stanford, and became a principal at the age of 27 years old. Luka believes that the future belongs to those who constantly and rapidly unlearn and relearn in their daily work and life.

We are excited to hand over to Luka to guide us through unlearning and relearning about the possible education futures. Welcome, Luka.

LOUKA PARRY:

Thank you so much, Amy. and no pressure, colleagues. You know what a topic. What a topic to be tasked with today to try to delve into the future of education, the possibilities and provocations. And I also just want to extend my respect to the elders past and present that have cared for this country, that I'm coming to you from as well here on Wurundjeri country of the Kulin nation. There is something about understanding the future and our understanding of the past that's really closely linked, and I've been really reflecting on this, this quote that I saw recently from Churchill, those that learn only from their own generation are destined to remain children forever. So there's something about some of the signals and trends. And of course, all you need to do is turn on the television and look at any of the news to know that we live in a very complex world today. So, I'm going to try to stay pretty within some guardrails, though, because otherwise we can get completely off the reservation when it comes to topics like the future of education.

So here are my learning intentions and our success criteria as well. And so, what I'd love us to learn today, and what I've designed for us is an examination of signals, trends and future scenarios for education. For us to reflect on the shifting demographics, the technologies impacting our work, especially generative AI, which I'm sure you're all very familiar with, and to consider our own pedagogical mindsets as we educate learners across Victoria. How will we know we've been successful? Well, thank you for investing your time and your attention into this and you'll be successful. This would be a good use of your time if by the end of our session, you understand the relevance of emerging issues and themes for education specifically linking them together, you've reflected on the principles that underpin your approach to effective learning and teaching. You've increased your futures literacy through engagement with a number of frameworks and provocations to keep building on your impact as an educator.

And critically, you will have smiled at least once because joy is good for us. It's certainly good for our psychophysiology, which is going to be one of the key themes that I point to today. And you know what, colleagues, fundamentally, this is really my core learning intention. It's neurogenesis, neuroplasticity. It's the brain changing itself. And one of the most remarkable things about us being in education and doing the work we do, is that we are quite literally shaping the neurobiology of the learners in front of us. So, my ultimate success criterion is that your brain is changed by the time I've finished speaking, and somewhat into the void in this webinar format with some pretty big provocations, I think, at this moment, and who we're called to be and what we're called to reflect on in our work. I was given a whole set of different questions as well, and even some beyond this to consider in my design of this session. And I apologise up front that for some of these, I don't have a simple answer because I don't think there is a simple answer because these are complex questions.

They're not even complicated or simple. They're complex. So, I will try to respond to these, but not necessarily answer them and so that's kind of a bit of a caveat, but certainly a lot of interest here about the shifts happening at the societal level. The skills, dispositions, capabilities and AI enhanced future. What does that look like with AI transforming in industry? How do we respond in education in our classrooms? Where do we draw the line? We'll have a very interesting reflection on that. And then of course, Edtech and AI benefiting all learners equitably. Is that possible? If so, how? And then of course, what are tech advances mean for the future of literacy and language learning. And I am a drama and languages teacher by training, and so I do reflect on that quite often I have to say. We also are nested in a context here in Victoria be you an educator at a government school, at a Catholic school, an independent school, or even further afield here in Australia. And so, understanding the context in which we teach and that learning happens is critical.

And so here in Victoria, you've got two really clear models. One is the framework for improving student Outcomes 2.0, which I think was a fantastic update, if I might say to include learning and wellbeing as the central mission. Understanding that those two constructs are completely integrated in a learning process and then of course, those five elements around the edge. And this Victorian teaching and learning model, with its four elements of learning and elements of teaching be it planning, enabling learning, explicit teaching and supported application. And I'm going to support some of these and hopefully extend us beyond into the future of what might be coming. What do we hold on to and where might we evolve? It doesn't matter what school you work in anywhere in the world, and I've been very fortunate to travel to almost every continent except Antarctica, including for work to try to understand what are different systems doing? What does a high performing system look like? What are the challenges?

And I would put to you that these five challenges or these five opportunities are faced by every single learning organisation in the world. The future of work. If the workforce is changing, and one of the missions of an education process in K-12 is to prepare young people for work. What needs to shift? Innovation, capacity. How do schools foster initiative, resilience and entrepreneurial spirit? Educational attainment. How do we ensure that we get good education outcomes for every learner, especially those on the margins? Mental health. What can we do to promote mental wellbeing and reduce mental health difficulties? Because they are presenting more and more across our society and that means more in schools too. And then social cohesion as well. How do we disagree better? I think is a really critical piece. So, anything titled The Future of... as a futurist, an education futurist, I would reflect, well, we have to be a bit more specific. So, a future for who or for whom? The future when?

What kind of future? What scenario? The future why? Our rationale. And the future how, which is strategy. So, in terms of demographic horizon, scenario, rationale and strategy, those are kind of the five different pieces that again, are going to be woven into this presentation today. So, the first one is future who. Well, what I'd like you to do is just to reflect on who you are and the era that you were educated within. And so, for me, I'm a Gen Y. I'm a millennial. And so, my experience across different horizontals in terms of technology and in my experience in education were different from the Gen Xers, the baby Boomers, the Gen Zs and the Gen Alphas. And of course, everyone on this call likely is a baby boomer to a Gen Z. There's no Gen alphas because they should be in school or on holidays, I guess, depending on where you are. And again, Gen Beta are being born this year. And so just think about the different elements that have implicated the way that we've grown up, the way that we've communicated with technology, the different layers, the way that our cognition has even been impacted or our social connectedness.

And at the learning future my fantastic colleague Doctor Ann Nock talks about these four elements that make a school a school. The learner experience, professional culture, the management and systems and spaces, places and resources. And she mapped her learning experience as one that was passive and individual. Her professional culture for teachers as content driven, talk from the front of the room. Very control oriented. Management and systems as herding efficiencies. I always kind of laugh a little when she reflects her own schooling experience where they were taught to march and they would march dutifully around the yard. And then this idea of uniform classroom environments single individual desks all facing the front in a very kind of transactional approach to education. Now, that was her experience as a baby boomer. And what I'd like you to do, just for a brief moment, if, is to reflect on your own educational experience. Because what we know from some of the research around invisible pedagogical mindsets from the Brookings Institution is that we often teach the way that we were taught, or there are implicit mental models that we have that inform our approach to learning and teaching.

And it is just the case that as educators, we're working with young people. And so, our ability to empathise and to co-design with them, to understand their own perspective as part of the deep student teacher relationship is such a critical point. And so, this is just a little provocation that over time, how do you think learner experience, professional culture management and systems and spaces, places and resources have shifted in education systems because they have. And the question is, have they shifted in the right ways, or where have they been really effective and where have they not yet been? So, it's just a wonderful provocation that we like to use. What could the future of education be? Well, it depends when we're talking about because the future of education tomorrow is very likely going to look like the future of education today. But the future of education in 2040 or 2050 or even 2100, well now we're into the realm of speculative design, and it's a fantastic kind of space in foresight, which is different from forecasting.

Foresight is really about multiple possibilities, understanding multiple scenarios, world building into our preferred future, was forecasting might be trying to analyse and predict. And I'm not a forecaster, but I am a someone that operates and deploys strategic foresight as part of my work with schools and with education leaders. And so, what we're looking at here in front of us is the three-horizon model. And this was really brought to bear by sharp the theorist. But of course, it's been hijacked by McKinsey and others. And the point is we are always operating at the first horizon. But whenever we are implicating the future, be it a strategy, be it as planning or lesson designing for next year or next semester or next term it's trying to understand which horizon are we actually playing in. Horizon one, which has a high degree of strategic fit with the external environment. But of course, horizon two is kind of incremental adjustments, but also some transformational experiments. And horizon three represents the emerging paradigms, the ideas and the innovations.

And so, it's always the case that in the near future and the far future, there are signals and trends that we can identify that are going to impact our current work. And that's why our work changes over time. It's also why we see huge shifts in the workplace or in industry, where you see entire companies go out of business because they failed to look to a third horizon and failed to step into a second horizon, be it Blockbuster or Kodak or just a number of companies that failed to do that. And so, there's a really lovely quote from William Gibson, who's an author and coined the term cyberspace. And it's that the future is already here. It's just not evenly distributed. And so, if we start to think in this way, what we realise is even in our own school, there are pockets of practice that represent the future. Even in our own practice as educators, there are pockets of practice that represent our future state of being a high impact educator or someone that can be even more effective, inspirational, engaging, motivating be that in knowledge, skills or disposition.

And I think it's really important to realise that we are in a remarkable, remarkable moment of change colleagues. It's terrifying and very exciting simultaneously. It's almost an age of paradox if we were to put it in that language, because we are no longer in the age of the computer. My father bless him, still complains about computers and why they don't work and his computer era. And I have gently remind him that the computer era, the third Industrial Revolution finished in 2015, one decade ago. And so, this idea of the automation of manufacturing, of just computation itself, being able to augment our workflow, bring them into education, the access to the internet that era that's already happened. What we're in now is actually the fourth industrial revolution. It's a cyber physical system convergence. It's where we have exponential technologies that are starting to converge. So, you have synthetic biology, and you have artificial intelligence and those things coming together. And when you do, you end up with personalised medicine.

This is the kind of era that we're in. It's filled with possibility, but it also challenges our own mental models in education. The mental models that that say, well, knowledge is what matters more than anything else. And don't get me wrong, knowledge is a prerequisite. But the case I'd put to you is that it's not sufficient anymore. It's not about just what we know anymore or what we can show we know. It's about what we can do with what we know. That applied nature or what we call transfer near and far transfer. And so, this idea of learning to learn or meta learning and meta cognition becoming increasingly important in our work in systems, adaptive quotient or adaptability, our capability to shift in an agile way based on new information and the creation of new value. And I just love this, that schools are most powerful when they enable young people to create new value. And why would they need that? Well, because the career ladder, the single industry, that's an old paradigm as well, just like a multi-generational industry or multi-generational job were now for a young person, if they have a social media account, effectively they have their first job because they are their own micro media company, for better and definitely for worse as we see here.

And so increasing complexity and with that increasing complexity comes a change in skill set required for employability and for the jobs of the future. And this is some work that I often speak to by the World Economic Forum. It's the Future of Jobs report. This gets released every year. And so, all I would say about this is that... You can see there the top ten fastest-growing skills by 2030. The top three are technology skills. But number four is cognition, it's creative thinking. And five and six are actually self-efficacy. It's resilience flexibility, agility, curiosity and life-long learning. Leadership and social influence, how do you lead a team? How do you bring a group together? Talent management analytical thinking and environmental stewardship. And this is coming from the pre-eminent group that represents industry in our world, a private group. And so even if we just thought education is about preparation for the workforce, we can make the case pretty clearly that there are some significant core skill shifts for that workforce.

And so what does that mean for us in the way that we design? The other piece that I must talk about, of course, is the new evidence that is being communicated to all of us in education and society about the impact of a subset of technology on, I would say, mental health and also cognition, critically cognition. And so this is a fantastic book called The Anxious Generation, which was released last year by Professor Jonathan Haidt, he's at NYU, he's a kind of pre-eminent psychologist who's written a number of books. And he's also a fantastic communicator, which I think is why this book has been so impactful. He talks about the four foundational harms that come from a phone-based childhood in this age of social media. And they are sleep deprivation, you know, where we know that healthy brain development and good attention and mood for the next day is an outcome of good sleep. But heavy screen media use creates shorter sleep duration. Even Netflix, when they look at their competitors, they even list sleep as a competitor for when you're in this attentional economy, that is exactly right.

Addiction smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle delivering digital dopamine 24 over seven in this response loop. Trigger action variable reward investment the hacked model. And again social media companies know this very well. But their business model is built on capturing attention. And so the teen brain for those of us that are middle school educators or high school educators, you know, we know that the prefrontal cortex is less developed and it's dependent on emotion, memory and reward systems. And so in some ways, we're more easily tapped into those types of loops, especially when you talk about self-esteem versus social esteem and the kind of individuation process. Attention fragmentation also really significant challenge. You know, constant alerts. If we're in a flow state of learning deep in a learning experience, and we get bounced out of that by an alert, it can take us up to 20 minutes to get back to that flow state if we are even able to get back there due to time constraints.

And then lastly is this idea of social deprivation. You know, this idea that is kind of social anxiety by nature or by design. And I think there's a really interesting conversation happening at the moment where even when young people are in social spaces together, they're still all on their phone, you know, as a Canadian college student says, he goes to a lecture theatre and 30 students are in complete silence. No one's communicating. No one's connecting. What kind of implications has that got for the young people that we educate? And then just to pull out and kind of start to double-click on the generative AI piece somewhat. This is a really interesting article from Harvard Business Review that came out last month on April, in fact. And it looked at one year's development in terms of the use cases for generative AI. What are the themes? And what's fascinating is that this personal and professional support theme has become highlighted, that the top three use cases today colleagues for ChatGPT number one, therapy, companionship.

Number two, organising my life. Number three finding purpose. Number four enhanced learning that might be good for us. Generating code for pros, generating ideas, fun and nonsense, etc. etc.. And so I think it's just really interesting to note that the number one use case is therapy and companionship, and that's got some implication for us as one of the key institutions in society that represent the social fabric of a community, a place where people convene, come together, learn, grow. So, let's look a little bit at education now. And there is no singular feature of education. I'm sorry to tell you, there are only scenarios for the future of education we might say there are futures of education. And the reason for that, and here's a lovely mental model that I always share in my work, and it's the cone of possibilities or the futures cone. And this is crafted by Joseph Verreaux as part of a generic foresight process framework. And we are here today, 2025, you know, June 23rd. You know, we have so many possible futures ahead of us that all of them are possible.

But then when we start to discern and use analytical thinking. We start to go, well, actually, these are the ones that are plausible. And then if we were to change nothing at all and had no strategic plan or teaching and learning framework, we just end up at the probable future. So, in my view, all good strategy is about articulating a vision and a future state or world, building that future state and then arcing your practice or your organisation's work towards that preferred future. And so to cite some of my favourite work in this space, this is the OECD's four scenarios for the future. And well, the future of schooling specifically. And what's interesting about this work. And I recently interviewed one of the co-authors of this for the Learning Future podcast which is a podcast that I run is that we we all have our preference. And for most of us, it's schooling extended its Participation in formal education continues to expand. We keep opening more schools. We keep building classrooms.

Australia's population continues to grow. International collaboration and technological advances support more individualised learning. The structures and processes of schooling remain. That is a scenario for the future of schooling. And for many of us, it's probably our preferred scenario because it means we don't have to change as much as some of the other scenarios would have us. For example, scenario number two education outsourced. This is where traditional schooling systems break down as society becomes more directly involved in educating its citizens. Learning takes place through more diverse, privatised and flexible arrangements, with digital technology a key driver. We see these signals in terms of the growth in home schooling or the growth in micro schools. This idea, or the idea that you will be educated at a community level rather than at a, you might call a civic level by a government institution, really interesting scenario. Scenario three schools as learning hubs. Schools remain, but diversity and experimentation have become the norm.

Opening the school walls connects schools to their communities, favouring ever changing forms of learning, civic engagement and social innovation. This is the idea of a school being open from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., where the school itself is more represented as a learning hub. And so you have adult classes happening after hours. You may even have things like co-working spaces from past alumni housed in the school in some way, and it becomes this local hub of constant learning activity. It's a very interesting concept and scenario. And number four is learn as you go. And this is a really interesting scenario because it's where education takes place everywhere, anytime. And that's the case now. Except what I'd say is learning takes place everywhere, anytime. But in this scenario, the distinction between formal and informal learning are no longer valid as society turns itself entirely to the power of the machine. Some very interesting things happening, of course, with big tech companies. And their approach to this in 2040, will there be a young person who says, ah, I attend Google Academy or I went to LinkedIn learning.

And the whole idea is this the platform is your schooling experience. Interesting, definitely challenging for me as a human centred educator, maybe for many of us. But of course, understanding that these scenarios are ones that we must consider and look at because we may have some system controls and guardrails and Incentives and initiatives. But we are also part of a global or regional network where school is being reimagined. I think in front of our eyes. So, what then? Well, what should we do depending on all four of those scenarios? Well, here's one claim I would make that any future ready learning includes more than just a narrow set of knowledge, or a set of skills, or just character. It must include all of them as a Venn diagram captured in meta learning and metacognition. And to be able to take a metacognitive view of your own life or your own learning, I'm going to talk about why that's even more important now than ever before as we delve into the generative AI picture. And so this is wonderful work by Charles Fadell and his team at the centre for Curriculum Redesign.

Again, he's also been a guest on the podcast, which is great, and I've learned a lot from this man. He's just a really brilliant inventor and thinker. And so this idea is that all education systems globally must pay attention to this, what he calls four dimensional education model. And so it's knowledge meets skills meets character wrapped in meta learning. And the new inclusion actually last year that was added to this model is the motivation triangle. And so if we take a generation that has been effectively primed through dopamine hits in extractive technologies, all of a sudden motivation becomes even more important aspect for us to consider in our design of education experiences and environments. What's the purpose? What's the intention? Do they have agency? Are they able to initiate their own learning based on my design? And how does this implicate my identity? As we know from some of the culturally responsive work and I began my first classroom was in a very remote Aboriginal community.

So, that cultural piece for me is just was made so clearly obvious. Who am I? What do I get to do? What is this for? Those are the three questions under the motivation triangle. Who am I becoming? What does it mean to be a good human being character? What can I do in the world, in the community, in this lesson the skills and the knowledge? What do I need to know? What's important knowledge, a threshold, reading comprehension, numeracy skills all critical, but also the floor, not the ceiling as this model would put. So especially those kinds of models become even more important when we start thinking about how AI is already shaping our learning experience. And I know that for those of you in Victorian government schools, you would have had a number of sessions with practitioners who were showing how they're using some of those technology tools in the learning process itself. I'm going to stay pretty high level today. But I wanna make this point, and I learned this from Salman Khan, who I worked with actually last year for Edutech when he came to Melbourne.

And it's Benjamin Bloom's Two Sigma problem paper from 1984. And what's so interesting about this paper is all those time, all those decades ago, Benjamin Bloom, of course, made Bloom's Taxonomy. That's why he's most well known, is that the Holy Grail in terms of mastery learning or tutorial instruction, is this idea of the two sigma problem that the difference between conventional approach with a bell curve to achievement, where you're teaching one teacher 30 students, and a tutorial which is a one to one? Of course, we know as teachers when you're working one to one, you can move really quickly. You can check for prior understanding. You could really individuate and differentiate. You don't even need to differentiate because one learner. And so this whole concept of differentiation is us trying to move that bell curve for everybody so that they can achieve better. AI, one of the hypotheses behind generative AI as a use case in education is that when and I`d say if when we get these kind of high fidelity tutors and they're involved and implicated in learning processes, we will get closer to this one to one two sigma problem solution, which I think is just absolutely fascinating to consider.

But it's not yet clear. Colleagues, it's not yet clear how these systems are gonna start impacting because I don't know what the technical term would be. I would say dog's breakfast, probably in terms of what's happening in the education technology space. It's the Wild West in some ways, all these different pieces, money to be made. Let's spin this thing up. This souls are teachers problem. I would say we need to be very cautious and discerning, and definitely check the ethical lens of any tools and technologies that we're using with in alignment with actually, the Victorian guidelines for the use of generative AI in education based on the Australian framework. So, there's different scenarios though here, you know, teacher only being one of them where it's just analogue teacher controls. That's great. Teachers running the whole thing versus full automation. And this is really where the teacher isn't involved at all anymore. The technology controls all the tasks automatically. And that it's adaptive learning.

It becomes an intelligent tutoring system, which is really interesting. And in some ways, that's what it's trying to replicate the wonderful work that a teacher would do but would never have the time to do, because we could not resource a school with one teacher for every student. Well, now we might be able to resource the school with a tutor for every student. This is definitely happening in different systems around the world. And so the case for adaptive learning can be made at two different levels. One is the learning time reduction. So it's just faster. And the other is self-pacing. And so with self-pacing it means I can learn things when it's and I learn them at a deeper level because I'm not missing out. I've taught the lesson. So you missed it. And similarly, for those students that are moving quickly, they can actually increase the level of learning. So and this is where that equity question comes in. Right. The ability to give every student what they need, including the additional supports or the assistive technology space.

There is an enormous amount of potential for that. Alright. I had a great chat with Dylan William last year, and we talked a lot about AI. And I probably need to have another one because so much has changed in 12 months. But one thing he said that really struck me was around homework. And he said the traditional model for homework where you grade what the students bring back with them on paper is dead. I was like, OK, well, that's a contention. Let's talk about that. And of course, he's a pretty compelling individual. And so at the end of that conversation, I really had kind of agreed with him because he makes the point that already some of these AI model performances are better than human beings, better than any single human being. Narrow intelligence tasks. AI is already outperforming across the board human beings. It's not yet outperforming us at general intelligence tasks. And depending on what task that is, there's still some time to go. So, that by the way, was AI passing AP and SATs and everything else can pass the bar exam, etc..

Why does this matter? Well, because thinking is hard. Thinking is really hard, colleagues, we know it. We do it every day in our classrooms, thinking. In fact, we have 30. Or if you're a secondary teacher, 150 brains moving through your classroom, right. And so there's this wonderful paper called The Unpleasantness of Thinking. A meta-analytic review of the association between mental effort and negative affect. That is a negative emotions. And so what's really clear, and this is so important for us to understand, is that the heart of our students work the worst. They're gonna feel right. And that the reason for that is the brain seeks efficiency. It seeks heuristics, shortcuts. So, we have fast thinking, slow thinking, you know mode one, mode two. And so this is really interesting because if I can just pump something into my ChatGPT or my custom GPT that I've built based off an LLM large language model, why would I not do that? It's a really interesting question. And there are some people out there, and I would say they're not usually teachers that say, oh, if I can do everything, why do we need to learn anything anymore?

It's the same argument we used to hear with the skills versus knowledge folk. Oh, you don't need any knowledge anymore. You can find knowledge on Google. You just need skills, we just need skills. Anyone that's kind of talking that language, I don't think really understands. Threshold and context. You need enough knowledge to ask the right question, to discern, to think critically, to apply that knowledge meaningfully. As they've put again here in this fantastic book that I've been referencing in this presentation, education for the age of AI. And again, it's that, as you see, it's the four-dimensional model from Fidel et al. This is a viral now viral study that came out last week from MIT. I'm just giving you the main insight here, because last week, MIT released this study that tracked 54 students with an EEG brain scan for four months and had them in three different groups. One group just, you know, use everything for AI. One group started with the brain and then used AI, and the other group just used the brain.

Now, the main insight here is cognitive debt. And so when you use an AI assistant for essay writing, what happens? Well, students who use just ChatGPT couldn't quote their own essays minutes after writing them. Finding number one. So the question is, how do we know learning has taken place? Well, they can't even recall the product that they put forward as evidence of their learning, which was the essay, right? Brain connectivity systematically decreased based on external AI support. So the more that we're using AI to support, the less our brain activity human teachers could reliably identify AI written work without being told about the study conditions, so we could tell still what was AI. And brain-only students had the strongest neural networks. Search engine users were in the middle. That was the second group, and ChatGPT users had the weakest. So, students who built thinking skills first and then used AI showed increased brain activity compared to the AI-only users. In fact, they showed increased brain activity across four different brain waves, which are the ones that we want.

And so this is really interesting. So it's about sequencing. Yes, we wanna use these technological tools because they're incredibly powerful. But I don't think we need assistance for writing essays, because what's the point of writing the essay? It's to learn. So what we need is a tutor or semi-Socratic approach so that we are actually learning the content being prompted by this tutor. So that's a really interesting piece. Main insight: cognitive debt. And it's the sequence with which we introduce a tool that, at least with this study, which is making big waves, claims. So isn't that interesting? So here's another piece, right? This again underlines the case for rigour, but not rigidity. We shouldn't make learning easier. The point is to struggle to grapple with content with new ideas. The zone of optimal confusion. I've heard it called before. Someone asked that question about what does this mean for literacy and for language learning? Well, as we know that learning multiple languages, for example, increases your executive or improves your executive function skills.

And so there's this idea then, that it's not just about learning content in a transactional way, so that needs to apply. It's how well-developed is your self-regulation and executive functioning of your mind. How much knowledge do you have at the threshold level, so that you have just enough to ask the right questions, but not too much where it's inert? And this is, I guess this is the tension that we see in curricula right now. OK, so what do we do? Now what? Well, so what? What do we do? And what I'm going to do is talk through our heuristic, right? How kind of ABCDE, the 5 principles that we think do underlie the future of education, regardless of whatever scenario might take place. I hope you're all still with me. OK, so I'm gonna start with A. A stands for agency. And the reason agencies really are of interest to me is not just because of self-determination theory and the work on autonomy or anything else. Although I do take that quite seriously. It's because the more and more research comes out, the more we realise that if we just have a ladder against a wall, and that wall is knowledge acquisition solely.

We've kind of missed an incredible opportunity with our young people, and that's that we might have achievers, but those achievers actually don't know what to do with that achievement. And so this is fantastic work from some colleagues, Jenny Anderson and Rebecca Winthrop. Rebecca is at the Brookings Institution as well. And they looked at four modes of learners, right? Passenger, resister, achiever, explorer. Now I would say some of the evidence-based pedagogical models that we have there are about engagement. It's about engaging. You don't wanna overload people too much, you know, 'cause we know that cognitive load is kind of tops out, so you don't want to ask them to do 20 things at once. We want to engage them to scaffold, you know, and that in some ways, using explicit instruction is a great way to help do that scaffolding piece. But if that's all we do, we might just be getting passengers and achievers. You know, the resisters. Those are the people and the young students that we would all know.

They're the ones that are very high agency, but they're just not engaged. They're either bored or they're disenfranchised or they're disengaged. Student. And we have some really horrific disengagement data in Australia. And it's not just us. It's pretty global. So my question to us is how do we move our orientation from achievers to explorers? Now, explorers are still highly engaged, but they are also initiating their learning. In some ways, they have more ownership over that learning. It's not being done to them. It's not I do, we do, you do, it can be you do, I do, we do. You know, and actually playing somewhat with that sometimes lock step is a really interesting way. And some of the interesting ways to consider this productive failure, for example, is a really interesting field of research that I follow quite closely. There's some evidence that shows productive failure is more impactful than even explicit instruction when it comes to remembering some of the deeper constructs. And, you know, we'd probably say that's recognition of prior learning.

It's trying to get people to activate their knowledge system before we introduce the ideas. It's more about learning than teaching, if I can put it that way. And so just to bring this point really home, because I know that right now and a lot of the approaches that are happening here in Victoria, you know, they're great. They're evidence-informed. We should think about the map of our pedagogy. And so what you're looking at here is somewhat complex, but these are the four quadrants that Michael Bunce, who's a lecturer at Flinders University in South Australia, has put together. It looks at knowledge exchange from explicit to implicit and looks at an agency the locus of control from extrinsic, i.e. teacher-directed, to intrinsic to student student-directed. And the point I would make. I won't go into this in too much depth. We can look at content, process and context. Down the bottom, which represents those Venn diagrams, is that we wanna be moving through all four quadrants. We absolutely want structured instruction, content-rich, a little bit of process, and contextually relevant.

But then, of course, we also wanna move into the intrinsic and explicit space, the semi-structured space where it's content and context with process. And then the emergent space which is this is actually where content plays a backseat. And it's about, well, what can we do? How do I transfer this? And this is the metacognitive awareness piece. And then the embedded piece, which is around contextual influence and kind of an assimilated capability, which is so implicit. So another way, just to put this work and again, this is kind of at the edge of my learning, I'm really interested in the future of pedagogy, to put it that way, is that yes, we want there to be transmission, you know, knowledge exchange. It's really good, right? Explicit, extrinsic. We want there to be a transaction. Here's what you need to know. I'm gonna give you this. I'm gonna train you in this way. And then we get to the middle which is around translation. And then when we start to get into the impetus that's being led by a learner, it becomes transposition.

Until finally when it's intrinsic and implicit, it's creative transfer. And all you need to do is look at a young person who is playing a musical instrument beautifully, to look at that creative transfer as a wonderful example, or look at somebody that's on their laptop. And, you know, completing an essay or an assignment in a group setting and just really kind of masterfully doing so. That's already in that creative transfer space. So it's just a really interesting piece to think about A for agency. B is for belonging. So increasing the level of belonging in our lives, in our classrooms, and in our schools will have a really good impact on us and our learners. And you know, Melbourne actually has been a hotspot for this research. For quite a while, this is out of Melbourne University. But belongingness is a key predictor of mental health, influencing everything from self-esteem to overall life satisfaction. You know, it's just so clearly the case when young people feel they don't belong at school or belong in a classroom, their performance suffers and so does their mental health over time.

And it's the same for us colleagues. If we don't feel like we belong, we also feel that same disconnection. We don't perform well, as some of the research shows us on organisational cultures and high-performing cultures. C is for curiosity. Curiosity as a predictor of performance. Listen to the Hungry Mind. It's the name of this study. Intellectual curiosity is the third pillar of academic performance. Isn't that interesting? So it's this idea that curiosity will drive performance over time. And I think it was Richard Feinberg. The famous physicist says, Anything is interesting if you go deep enough. And so what we really want are deeply curious young people that are curious and creative with technology, not apathetic and consumers with technology. And, you know, it's like almost two interesting modes there that we might see. So this idea of a hungry mind. Is your mind hungry? And if you're a primary teacher, it's a great language. Do we have a hunger? Is your mind hungry today, students?

It's just a great way to think about that. Let there be curiosity. And I just wanted to put this up as well. I saw this recently, and it really struck me. I thought this is very interesting. So, just like we have nutritional advice and ingredients in our supermarkets. Is there a future scenario where we have cognition, facts and ingredients? And like how many cogitates would be used by doing this task, using this technology or watching a show? It's just a really interesting piece, right? The more that we're on uni channel, algorithmically designed platforms, the less cognition we're using. And it's a use it or lose it kind of consideration. You know, so if we've already overloaded ourselves before we even get to our school, because we've spent two hours on a phone as a young person getting there, what does that do to our cognition? I really do think cognition is under attack at this point, because it's cognition and attention that is the driver of cognition is a currency today. D colleagues stand for discernment in our Learning Future alphabet.

And this is a really interesting article in Nature, you know, Time to Expand the Mind. Our brains are already working at near-optimal capacity. We can't crunch more things in. We can't just think harder. What we need to do is think beyond the brain into what's called the extended mind. This is embodied cognition, situated cognition, and distributed cognition. This is all about how do we think better and well, considering the limits of our biological capability and how squeezed they are now, just in our days as educators, let alone in our students' days. The reason that really is so important is because we live in a world today that has so much information in it, and so much potential misinformation in it. This gentleman from Wolf News speaks more languages than I do, and he does so, of course, because he's an AI. He's an AI newscaster. And so we're already in this moment, colleagues. And I can't be more explicit about this. We are in this moment where we do not know if we are talking to a human being, or if we are talking to an artificially intelligent chatbot.

How do we know that? Because large language models pass the Turing test, the three-stage Turing test. In fact, what's so interesting is that ChatGPT was judged to be human 73% of the time, significantly more often than the interrogators selected the real human participant. So that's clear. These models are more human-like than we are. We judge them as more of a human being than we are when we're engaging with them. So we must be discerning about whatever a bias might be in a product, or whenever we're looking at any piece of information, any piece of media. Is this real or is this fake? Who would benefit either way? And finally, colleagues, is E for embodiment. And I really nerd out on this stuff. I gotta be honest with you. There is something about this AI era where everyone is really... Here's the latest tool and the latest video thing, and I stepped back from showing all of you those things because I'm more interested in the principled conversation underneath it, which is... OK, that's all well and good, but the real software and hardware that I'm also interested in is our human software and hardware, 'cause we work in a human system as educators and leaders.

And so our psychology, which is our software interacting with our physiology, which is our hardware, and for me, we have not paid attention to this, not our fault in education systems, because we've just inherited mental models that say, well, brain learning happens in the brain and it's about knowledge because we can test knowledge easily. And don't get me wrong, I am a nerd. I love knowledge so much, but it's what do we do with what we know and who are we as we do things with what we know. And clearly and critically today, especially when we look at mental health, us being able to return to our body, use our Interoception, understand what's happening for us emotionally in affective space, and then connect our affect to our cognition is absolutely a principle for the future of education. So this means paying attention to vitality, sleep, nutrition and movement, and energy management. And it definitely means positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and achievement. And that's Martin Seligman's perma plus V model, which I would note, it was perma.

And then of course, because Martin is a psychologist and a world-renowned one at that, and a psychologist also forgot the body. And so this body brain contract, you know, our brain comes from our physiology, how well we think it matters how well we are physiologically. The other great work is that... I've just created and put a really simple one here. Most of us would know Maybe some of you would do. Zones of regulation. Or you might do some other emotional intelligence or social-emotional work, respect for relationships, etc, it's to understand that if we want great outcomes for our young people, we must give them the tools and strategies to step into their window of tolerance and expand it to not be hyper-aroused, i.e. busy mind because of whatever and not hypo aroused. Apathetic, depressed, lethargic, numb, unmotivated. So, using mindfulness breathwork, physical activities, and other social strategies to help our young people and ourselves be in that optimal state as much as possible.

It matters now more than ever. And so if we can return to the idea of embodiment, and I think it is a return to look at, you know, lots of First Nation wisdom as well. It's not an invention. It's like a remembering. Yes, actually, we have a body that we ought to move, the more we move it, in fact, the better our thinking quality is. And so this idea of physical activity, and maybe it's because I am a PE-trained teacher, but there is just so much evidence that underpins embodiment as a principle for the future. So, now what? I just hammered you with a bunch of slides. And I hope you are following along. I'm really looking forward to a conversation with Amy on some of these ideas. Because for me, you know, it's not there's no silver bullets here, but there are small specks of gold might be able to bring together. These are some principles that I really reflect on in my work globally in education. And the first is we have to preference curiosity over certainty. It's OK for us to say we don't know yet, but this is what we're thinking.

And in fact, curiosity in my view, might even just be the neurobiological spark we need of all mastery learning. In some of the models that I look at for example, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang would say, unless you care about something at some level, it is biologically impossible to learn it. And she's a professor at UC Berkeley, I think, now, and an affective neuroscientist very interested in that bit. I've talked about rigour, not rigidity. And what we sometimes think is rigorous. It's not. It's just rigid. It looks good because it's all organised and there's a spreadsheet and lesson plan, but there's no real rigorous thinking happening. Young people aren't being called to reflect, you know. So, I think there's and we're not being called to reflect or enter into metacognitive strategies, which is one of the biggest high impact, high effect size strategies we can put into our work and our pedagogy. Executive function for the win. I've tried to be slightly playful with the language there, Amy, but really, if we can help our young people develop their executive function skills as we also teach them to read.

Teach them to write. Teach them to be numerate. We are setting them up to be effective because they can make good choices without executive function. It is not possible to make good choices because our rational mind is no longer online. We're in fight. Flight, freeze, Amygdala hijack. And that's especially important for populations that have experienced trauma in some level. We must be really, really considered in supporting sequenced, structured ways to develop executive function. I'm always kind of curious when systems are so obsessed with quality teaching. I love quality teaching. I hope I did some at some point when I was a practitioner in a classroom. But do you know what's better than quality teaching? Quality learning? And one thing that will be the case for us in education is we may need to understand that high impact instructional strategies are really important, but actually learning is happening way outside of just what I'm trying to instruct in a transmission or transactional way.

This is why the agency piece, I think, is really curious for us. It's not how did your teaching go? It's how do we know learning took place? That's a better question and a better frame of reference. People love data, especially system people. I love data too, but we should never be data driven. We should be purpose-driven and data-informed. What's the purpose? What do we believe in as a school leader? This is our strategic plan. This is our it's expressed intentions as a classroom. What kind of culture do we want? What's our purpose? And then of course, be as discerning as possible in taking in the rapid loops of data that we can to get even. And I think we'll get to continuous reporting eventually. The kind of end of year reports will be a thing of the past. The rise of self-determined learning. This is a reality young person, today, if you ask them honestly. They might say I learned more from YouTube than I learned in your class. Louka, now that that's kind of a bit of an ego bruise for me, but that's also an opportunity for us in education.

How do we guide, facilitate or use John Hattie's language? Activate our learners by using particular pedagogical strategies. Brain first, then IA, that's just one interesting principle to keep an eye on. So, yes, use AI tools, but ask the questions first. Get that brain active and start getting it linking. And then once there's enough threshold, bring in a generative AI tool to be able to extend some of those learners. I would say don't start with AI. That was a real change in my own mindset when I read that study. And then this last piece, BQ, EQ, IQ, AQ, what on earth does that mean Louka? What it means is this simply, our ability to be adaptive in the world and be especially in terms of adaptive leadership, goes there's a straight line all the way back to our body quotient, our psychophysiology, our physiology. You know, even things like parasympathetic nervous system. So, focusing on BQ breathwork vitality nutrition implicates emotional quotient which implicates how quickly I can learn which is IQ, which implicates how quickly I can adapt and change.

And so I've got two slides left. Amy, we're right on time. I'm amazed with my own ability to do that, it's not always the case. This is one I wanna leave you with. Right. And this is adapted from Peter Senge, the fantastic systems thinker from MIT. And I just think in the day to day role that you play as an educator, as a leader, it is. So, there is so much happening that often we'll get into this problem. Fixed loop. Right. An event reaction. You're just constantly in reactive mode and I commend you for being in reactive mode and being able to sustain that and get through a day. What the future of Education calls us to do. And this is kind of, this is the luxury I have in having the time to have my eyes on multiple horizons. Working alongside educators in schools is to look at the strategic, the patterns and trends. How do we observe them, the systems and structures, how do we redesign them, and the mental models, including my own? How do we transform them? What is learning for? What is education for in this moment and into the future based on that?

What do I need to do? What are my young people need to do? What do they need to know? And colleagues, keep going. You know, this was a quote that was on my wall. It's still one that I put at the end of every presentation, largely for myself. But it's also for you. It's that we cannot get through a single day without having an impact on the world around us. What you do makes a difference. You just have to decide what kind of difference you wanna make. The fantastic living hero of mine, Dr. Jane Goodall. It's idea that it can sometimes feel like a grind or you're not making an impact. You change your young, your learner's brains every single day. So, thank you for what you do. Thank you for your attention as well. To try to consider some of these really big, you know, threads that I've been trying to weave together here today. My final offer to you is we put out a loan letter once a month if we get around to it, but in that it has some of the we think the most important things for us to pay attention to.

The podcast is my way of continuing to learn and stay at the forefront of this conversation, and then keep showing up for learners every day. It really matters greatly. Thank you so much.

AMY PORTER:

Thank you, Louka. We, I'm just inspired. The executive functioning for the win is a big one. I say, because Is often particularly working with teenagers. We know executive functioning is something that goes out the window a little bit. It goes a bit offline. And we need to, as educators, really strategically bring it back online. So, thank you. I love that saying I was busily typing and writing things down from what you said. Look, we have three questions. Let's see if we get through all three. But if not, I'm gonna sort of put them in order of what I think you've probably covered, the, that people are interested in... I'll leave to the end. But the first one is what common patterns do you see in how education systems are preparing students for an AI integrated future? So, what are the common patterns that you see in schools? But also where are the biggest gaps?

LOUKA PARRY:

It's such a great question. A couple things on that, Amy, and thanks for the question. Number one is this is so new. You know, it was ChatGPT 3.5 came out, whatever it was, November 20th 21 or 2022 or something, you know. And so for an education system to even be responding to this is kind of pretty remarkable. There's some great work happening nationally that I've been close to, that conversation with the chief information officers of Australia. And there's three kind of use cases that are emerging. The first is this idea around a tutor, which is interesting, like a tutor for the learner themselves. The second is for a teacher assistant, which is an interesting use. Again, the third is kind of like a a general assistant AI system tool. So, you're a principal, you wanna find a thing rather than having to search through you just ask this kind of GPT now what do I think about how, like an AI integrated future and how systems are preparing young people for that? My honest reflection is it's pretty difficult to do that as a system at this point in time.

Right? Enormously complex human systems, but there are some promising lights I'll point to. Number one is the work that's happening in South Australia, for example, with Edchat. Which is an AI tool to, it's based on an LLM that has guardrails. And so that's been brought in. So, every teacher has access to that and is using it to augment their learning. Now, notwithstanding we don't want assistance for our students. We want tutors for our students. Otherwise they miss the learning bit, Amy, that we're all, like the, that the artefact or the assessment is meant to assess. And so I think something around the future of assessment is an enormous conversation as well. We cannot just rely on a single artefact at the end of that. So, I would just say be curious at whatever level you are. I think this goes all the way up to the fractal of a system. The secretary, the director general needs to be as curious about this as the student in year six. You know who's also starting to integrate these tools.

But these tools must be used to augment and support learning, not create cognitive shortcuts or cognitive debt, which actually diminishes the learning process. And again, we are, these studies are coming out, you know, every every week or so. It's trying to keep across those. What I would see in the 20 in a world of let's talk 2030, let's try to answer this question. I would expect that we would have a learning tutor for every student that is safe, that doesn't take the data and push it into a commercial model somewhere, as some of the main free models do now. That is actually got the curriculum of the jurisdiction built into it and the developmental continuer as part of it. So, then I literally do have a teacher assistant. We'll learn like a learning tutor. You know that I can utilise as well. That is asking me questions. Checking for understanding. It's not doing my work for me, which is what is happening, I think a little bit at the moment. So, it remains to be seen, but I still think we're gonna have a tutor and our role as educators.

We will also have an assistant. And I'm saying a five year timeline. It might be faster than that. I mean, it's already the case in South Australia and in New South Wales with edu chat. So, I think Victoria will that'll also come in at some point in time. But the whole idea is how do we get to do the work that really enlivens us, the high impact social dimensions of learning. Right. And then leave some of the deliberate practice, even some of the assessment stuff, the stuff that we don't really love to do as teachers to some of those models. And I'm pretty confident that there's some really emerging, promising use cases in that space.

AMY PORTER:

Thank you. I love what you're saying about preferencing teacher time for the actual impactful teaching and pedagogy and interactions with the young people we work with. The last question we have is your bio mentions the future, that the future belongs to those who can rapidly unlearn and relearn. So, what do you perceive to be the enablers and barriers for schools around this unlearning and relearning?

LOUKA PARRY:

Yeah, well, I mean, I could ask you the same question as a fantastic leader, you know, you would have seen multiple waves of change. I'll start with a, with one of my favourite quotes. And it's from Keynes, the Economist. And he said it's not so much embracing the new ideas than letting go of the old ones. And so that's why I think the unlearning piece is so important. One one question that I often ask in person workshops, Amy, is when was the last time you changed your mind? Think of that moment. Explain it to me. Explain it to the person next to you. You know. And there's good protocols we use in education for this, too, like Project Zero stuff. You know, I used to think, now I think, you know, I think I wish I wonder, you know, like these are great cognitive like tools to help us. But the issue is we do not change as much as we think we do. Even for me, someone that's pretty well read on all the kind of, you know, heuristics and behavioural economics stuff, you can know all the biases and still be captured by them.

So, the unlearning piece is so interesting to me. It's why I think doing the identity work is really important. So, that it's not, you know, my job isn't. I'll put this to the, to this as a teacher example as well. So, we might need to unlearn what it means to be a teacher now. No one panic just yet, but I'll make this point. So, I'm a let's say, languages teacher, right? And so I have it on my badge. Languages teacher. Now, I think the I think that's a problematic framing because it somehow preferences languages is the most important part. And what I see emerging actually is the role of a pedagogue, which is I, you know, I'm a I'm a pretty good teacher, but I reckon there's some AI tools that will be even better than me that will be able to, like, directly inspire someone with a cool video and try and learn Spanish or Greek or whatever. And so what is my role become? Well, then I become like an language activator or a learning guide with a specialisation in. And just that change in framing means that I'm far less bound to have to be the knowledgeable other in languages and be able to do the stuff that I love to do, which is with other people, you know, with learners to help them make sense of the world, be inspired by their potential to change it, you know?

I think that's a really interesting piece, even the way that we think about the role of a teacher. I think we're gonna in the next 15 years in particular, I think that's gonna be under threat. And so that's all I mean, it's like, what are you letting go of in order to be born? Like, what idea, what mental model package you go? I used to think this, but I'm being I'm considering this and I'm terrified because I'm really associated with this aspect. So, the unlearning bit I think is, is gonna be a massive part. And it's why, you know, we talk about adaptive leadership or agility that those things are really about being able to navigate ourselves through a terrain to wayfind forward, not just lockstep, some linear path.

AMY PORTER:

Biologically, change is scary. And, you know, what do we implement in our schools in the future so that we can implement other things that are going to add value to the students in our lives? Well, thank you so much. Can I ask you just to flip to the next slide? Because we would really love for some feedback, but just to finish by saying thank you, Louka. Really inspirational and really opening that, you know, that taking some of the fear away about the notion of we educate and then we open young people up to I as a support tool. And I think that's the way most educators would really love to see that how we can use AI in schools and not as a supplement to what we do and not as the main instrument in education. And I thought that was really well put and really cements what a lot of us are thinking. So, just as we finish I know all of you probably silently giving Louka a little bit of a clap and thanking him very much. We do have a very quick survey. It's three questions. This helps us then plan the direction of our next thought leadership series.

So, if everyone can just take a minute to complete the survey, and I'll just finish off by saying Zai, Zion, Louka, thank you very much. Good luck with all your Mandarin learning. Three years of Mandarin in high school and I have about four sentences. So, you're a brave man, but I have met some people that are extremely fluent. And as a linguist, I'm sure that you're, you're enjoying the as you put the challenge of learning something new. And I hope there's some great AI tools out there that are supporting you in your learning around language as well. And if you just will just thank you there because we have met, hit right on 4:59 and I know that people have had a busy day and we're in the second last week of term. So, we do appreciate everyone joining us. And we'll send you off in with a lot to think about. And this recording will be available on the Academy's website. So, if you wanna go back and go through any of the ideas that look raised with it. So, thank you, Louka. And good night everyone.

LOUKA PARRY:

Thank you so much, team. Keep going.